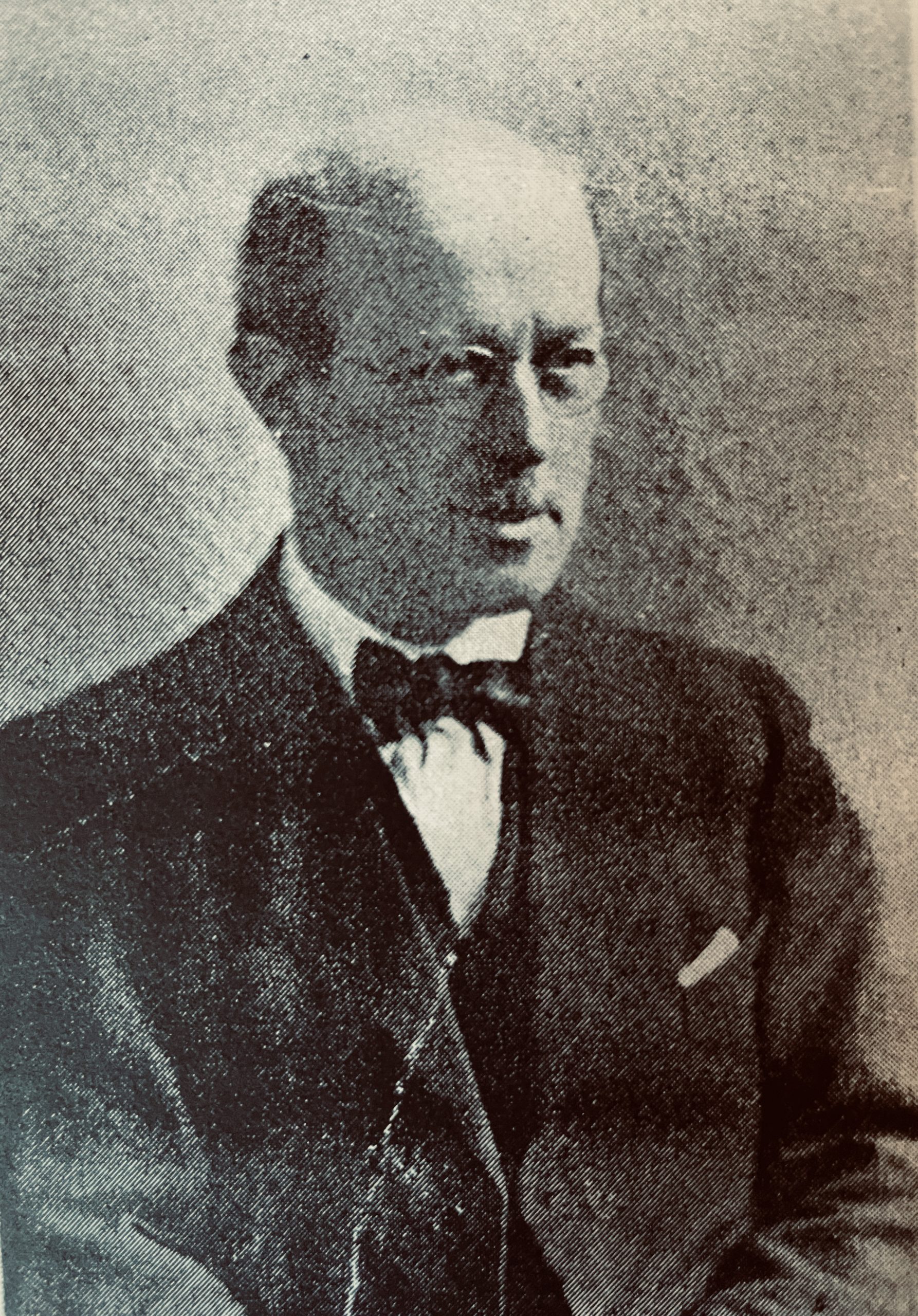

A legacy – Arthur Reginald Smith, ARA RSW RWS

High Fells

Most associated with the fresh and silvery watercolours of his native Yorkshire Dales, I was brought up surrounded by my Great Grandfather Arthur Reginald Smith’s paintings. As a child, we frequently visited my Great Auntie Barbara (one of his daughters and an accomplished artist herself) in Grassington. She used to speak about her father, and we regularly visited the places he painted and played in his beloved River Wharfe (the smell of wet wellingtons still conjures memories of that time).

Reginald as he was known, was born in 1872 and grew up at 70 Keithley Road, Skipton. From an early age he wanted to become an artist, however, he was discouraged from his artistic ambitions by his parents William and Hannah, (William owned the local pharmacy) becoming a primary school teacher at their insistence. Sketching trips and evening classes however led him to full time study at the Keighley School of Art, where he subsequently became an Art Teacher.

He married Alice Anne Wright at Bolton Abbey on Monday 9th August 1897, and they had three children, Mary Margaret in 1898, Henry Allen (my grandfather) in 1900 and Eleanor Barbara in 1909.

Spring-time, Buckden

In 1901, at the age of 29 he gained a place in the Painting School of the Royal College of Art and in 1905, he was awarded an RCA scholarship which allowed him to travel to Italy, where he studied for a year. For him to have given up a safe, salaried job to become a full-time artist was a massive step, especially with a young family. I have such admiration for Annie for so obviously supporting him in fulfilling his childhood dream. Given all that upheaval and for him to then leave her with two young children for a year, she must have been a very special person.

During the early part of his artistic career, he received commissions to paint watercolours of the private apartments at Marlborough House and Buckingham Palace from Queen Mary, and his watercolours are now in the Government Art Collection. During the First World War he served in the Artists Rifles. At the end of the war, the family moved back to Yorkshire buying Farfield in Threshfield (you can now stay in what was his old studio) and they remained there for the rest of their lives.

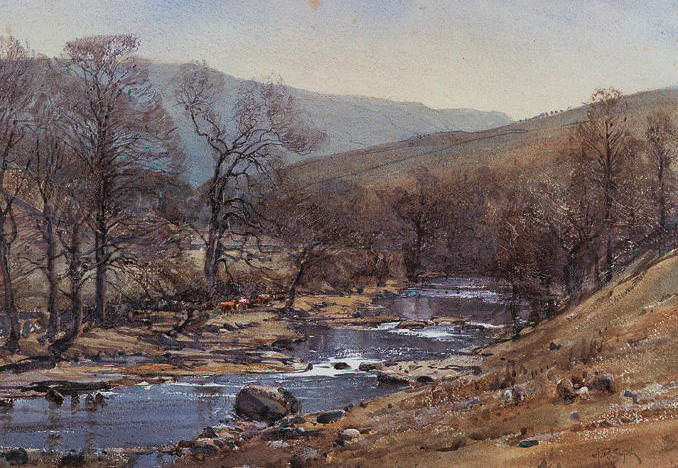

Langstrothdale

He was elected a full member of the RWS in 1925 and RSW in 1926. He also illustrated Halliwell Sutcliffe’s The Striding Dales (1929) and a reprint of W G Collingwood’s The Lake Counties (1932).

Most of his subject matter was drawn from the countryside immediately around his home. These were executed in watercolour and always painted in front of the subject. The subjects themselves seldom varied: views of the Wharfe, with its magnificent stretches of hills and moorland beyond, favourite villages of Kettlewell, Grassington and Appletreewick, direct studies of the river itself with its currents swirling around the stones of the riverbed. What changed significantly in each familiar view was his own response to mood, season and time of day.

He preferred subtlety to drama and frequently chose dusk and early morning to evoke the atmosphere of a partially deserted landscape. During an interview with John Marsh of The Dalesman in 1927 he said “…There is a certain tranquil beauty about the day when the sun is rising, something quietly lovely about the hills and river when the world is half asleep…”

These shimmering scenes of dawn and dusk were painted with a limited palette of colours. Broad but delicate effects were achieved by using a large brush which dragged the pigment over the paper, leaving isolated pinpricks of uncover ground that gave sparkle and vitality to all parts of the picture. The initial structure of the composition would be summarily but firmly indicted in charcoal. Sketchbooks were never used for working up into larger ‘studio’ works. His time in the studio was spent purely on the simplification and refinement of works painted during his long treks over the countryside.

The watercolours would take between two and three uninterrupted hours, and apart from high summer, he would paint out of doors all year round. J. Keighley Snowden writing for the Old Watercolour Society remembered that “…He put a little whisky in his painting water and stood on cork mats in the snow. Wind was his only enemy. All weathers else, morning and evening, autumn, winter and spring, were welcome allies of an absorbing passion…”

He found the heightened colours of the summer monotonous and confessed that summer reminded him of a “monochrome of greens”. Later he said: “…I think that the winter and early spring are the best times to paint the Wharfedale Valley, and most of my work has been done then. I find green a difficult colour to work in and much prefer the sober browns and greys.

Humphry Brooke, secretary to the Royal Academy wrote in 1970: “…The Wharfe is the only river I know which has had its own poet in paint. Reginald Smith never left it once he had settled in Threshfield… he was an interpreter of the Wharfe: it was an idyll of love covering the best years of his life…”

On the Friday 14th September 1934 he went missing near the Strid on the River Wharfe at Bolton Abbey, a notoriously fast stretch of water.

His body was found eleven days later by a local water diviner, who pointed to a pool fifty yards downstream from where his easel and painting bag were found. The police dragged the spot and found his body: he was 62 years old. Those eleven days must have been such torture for Annie.

As requested in his will his ashes were later scattered in the Wharfe, at Yokenthwaite in Upper Wharfedale.

Mary Margaret, Alice Anne and Henry Alan (My Grandfather)

My Mother, who was born in 1933, didn’t have any recollection of him although she believed she did meet him. With the threat of invasion, she was evacuated to Grassington in 1940 to stay with her grandmother, along with my uncle. Given Annie was a widow and in her seventies by then and had two young children foisted on her at short notice, Mum’s memories of her were only of kindness and understanding. They stayed with Annie for around a year with my grandfather and grandmother, who were dairy farmers, only able to drive up once from East Sussex to see them at Christmas 1940.

Annie died in October 1945 at the age of 77. We have a portrait of her in our hallway, painted by Reginald who clearly loved her, and she has a real air of serenity about her. Reginald was a man of few words by all accounts and loved to walk. Knowing what I know of him I think we would have got on well, both of us most content in our own company and being outside in the fields and woods.

I would have so loved to have met them both.

I hope in my art I can catch some of Reginald’s skill in portraying the essence of the places and landscapes that he loved and that I can do his legacy justice.

RIP Reginald and Annie

References and further reading on AR Smith